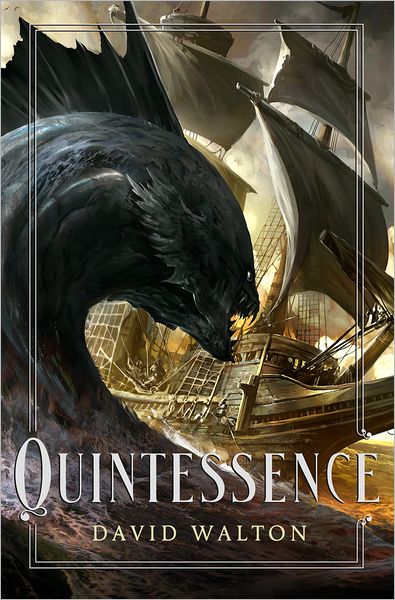

Because it’s Sea Monster Week, and we love giving you special treats when these lovely themes come along, we’ve got a special excerpt of Quintessence by David Walton. This book won’t be released until March of next year—March 19, to be exact—so you’re getting a look into the magical future!

Quintessence opens with an Admiral who has spent years at sea, his goal to prove that the west contained riches beyond England’s imaginings. The proof is safe in his hold, trunks full of gold, spices, and odd animals, and his ship has almost reached London — but then his crew informs him of an impossible turn of events.

By the time Lord Chelsey’s ship reached the mouth of the Thames, only thirteen men were still alive.

Chelsey stood at the bow of the Western Star, staring mutely at the familiar stretch of English coastline. The coal fire in North Foreland’s octagonal lighthouse tower burned, just as it had when they’d left, guiding ships into the sheltered estuary. The silted islands were the same, with the same sailboats, dinghies, and barges wending through the maze of sandbanks, carrying trade goods between Essex and Kent. After seeing the great Western Ocean crashing headlong over the edge of the world, it seemed impossible that these familiar sights should remain. As if nothing had changed.

“Nearly home,” said the first mate, the eighth young man to hold that post since leaving London three years before. He was seventeen years old.

Chelsey didn’t answer. He didn’t insult the boy by promising a joyous reunion with family and friends. They would see London again, but they wouldn’t be permitted to step ashore. It was almost worse than failure, this tantalizing view of home, where life stumbled on in ignorance and peace.

But he hadn’t failed. He had campaigned for years to convince King Henry there were treasures to be found at the Western Edge, and he had been right. The barrels and chests that crammed the ship’s hold should be proof of that, at least. Treasures beyond even his imagining, not just gold and cinnamon and cloves, but precious materials never before seen, animals so strange they could hardly be described, and best of all, the miraculous water. Oh, yes, he had been right. At least he would be remembered for that.

Black-headed gulls screamed and dove around them. Through the morning mist, Chelsey spotted the seawalls of the Essex shoreline, only miles from Rochford, where he’d been raised.

He shifted painfully from one leg to the other. It wouldn’t be long for him. He’d witnessed it enough by now to know. Once the elbows and knees stiffened, the wrists and fingers would lock soon after, followed by the jaw, making eating impossible. One by one, they had turned into statues. And the pain—the pain was beyond description.

They sailed on. Marshlands gave way to the endless hamlets and islands and tributaries of the twisting Thames, the river increasingly choked with traffic. At last they circled the Isle of Dogs and came into sight of London Bridge and the Tower of London, beyond which sprawled the greatest city in the world.

“Admiral?” It was the first mate. “You’d best come down, sir. It’s a terrible thing.”

Chelsey wondered what could possibly be described as terrible that hadn’t already happened. He followed the mate down into the hold, gritting his teeth as he tried to bend joints that felt as if they might snap. Two other sailors were there already. They had pried open several of the chests and spilled their contents. Where there should have been fistfuls of gold and diamonds and fragrant sacks of spices, there were only rocks and sand.

His mind didn’t want to believe it. It wasn’t fair. He had traveled to the ends of the earth and found the fruit of the Garden of Paradise. God couldn’t take it away from him, not now.

“Are all of them like this?”

“We don’t know.”

“Open them!”

They hurried to obey, and Chelsey joined in the effort. Wood splintered; bent nails screeched free. They found no treasure. Only sand and dirt, rocks and seawater. He ran his fingers through an open crate, furrowing the coarse sand inside. It was not possible. All this distance, and so many dead—it couldn’t be for nothing.

“What happened to it?” he whispered.

No one answered.

He had failed after all. Soon he would die like all the others, and no one would remember his name.

He tried to kick the crate, but his leg cramped, turning the defiant gesture into something weak and pitiful. God would not allow him even that much. Lord Robert Chelsey, Admiral of the Western Seas, collapsed in agony on the stained wooden floor. He had lost everything. Worse, he would never know why.

Chapter One

There was something wrong with the body. There was no smell, for one thing. Stephen Parris had been around enough corpses to know the aroma well. Its limbs were stiff, its joints were locked, and the eyes were shrunken in their sockets—all evidence of death at least a day old—but the skin looked as fresh as if the man had died an hour ago, and the flesh was still firm. As if the body had refused to decay.

Parris felt a thrill in his gut. An anomaly in a corpse meant something new to learn. Perhaps a particular imbalance of the humors caused this effect, or a shock, or an unknown disease. Parris was physic to King Edward VI of England, master of all his profession had to teach, but for all his education and experience, the human body was still a mystery. His best attempts to heal still felt like trying to piece together a broken vase in the dark without knowing what it had looked like in the first place.

Most people in London, even his colleagues, would find the idea of cutting up a dead person shocking. He didn’t care. The only way to find out how the body worked was to look inside.

“Where did you get him?” Parris asked the squat man who had dropped the body on his table like a sack of grain.

“Special, ain’t he?” said the man, whose name was Felbrigg, revealing teeth with more decay than the corpse. “From the Mad Admiral’s boat, that one is.”

“You took this from the Western Star?” Parris was genuinely surprised and took a step back from the table.

“Now then, I never knew you for a superstitious man,” Felbrigg said. “He’s in good shape, just what you pay me for. Heavy as an ox, too.”

The Western Star had returned to London three days before with only thirteen men still alive on a ship littered with corpses. Quite mad, Lord Chelsey seemed to think he had brought an immense treasure back from the fabled Island of Columbus, but the chests were filled with dirt and stones. He also claimed to have found a survivor from the Santa Maria on the island, still alive and young sixty years after his ship had plummeted over the edge of the world. But whatever they had found out there, it wasn’t the Fountain of Youth. Less than a day after they had arrived in London, Chelsey and his twelve sailors were all dead.

“They haven’t moved the bodies?”

Felbrigg laughed. “Nobody goes near it.”

“They let it sit at anchor with corpses aboard? The harbor master can’t be pleased. I’d think Chelsey’s widow would have it scoured from top to bottom by now.”

“Lady Chelsey don’t own it no more. Title’s passed to Christopher Sinclair,” Felbrigg said.

“Sinclair? I don’t know him.”

“An alchemist. The very devil, so they say. I hear he swindled Lady Chelsey out of the price of the boat by telling her stories of demons living in the hold that would turn an African pale. And no mistake, he’s a scary one. A scar straight down across his mouth, and eyes as orange as an India tiger.”

“I know the type.” Parris waved a hand. “Counterfeiters and frauds.”

“Maybe so. But I wouldn’t want to catch his eye.”

Parris shook his head. “The only way those swindlers make gold from base metals is by mixing silver and copper together until they get the color and weight close enough to pass it off as currency. If he’s a serious practitioner, why have I never heard of him?”

“He lived abroad for a time,” Felbrigg said.

“I should say so. Probably left the last place with a sword at his back.”

“Some say Abyssinia, some Cathay, some the Holy Land. For certain he has a mussulman servant with a curved sword and eyes that never blink.”

“If so much is true, I’m amazed you had the mettle to rob his boat.”

Felbrigg looked wounded. “I’m no widow, to be cowed by superstitious prattle.”

“Did anyone see you?”

“Not a soul, I swear it.”

A sudden rustling from outside made them both jump. Silently, Felbrigg crept to the window and shifted the curtain.

“Just a bird.”

“You’re certain?”

“A bloody great crow, that’s all.”

Satisfied, Parris picked up his knife. Good as his intentions were, he had no desire to be discovered while cutting up a corpse. It was the worst sort of devilry, from most people’s point of view. Witchcraft. Satan worship. A means to call up the spawn of hell to make young men infertile and murder babies in the womb. No, they wouldn’t understand at all.

Felbrigg fished in his cloak and pulled out a chunk of bread and a flask, showing no inclination to leave. Parris didn’t mind. He was already trusting Felbrigg with his life, and it was good to have the company. The rest of the house was empty. Joan and Catherine were at a ball in the country for the Earl of Leicester’s birthday celebration, and would be gone all weekend, thank heaven.

He turned the knife over in his hand, lowered it to the corpse’s throat, and cut a deep slash from neck to groin. The body looked so fresh that he almost expected blood to spurt, but nothing but a thin fluid welled up from the cut. He drove an iron bar into the gap, wrenched until he heard a snap, and pulled aside the cracked breastbone.

It was all wrong inside. A fine grit permeated the flesh, trapped in the lining of the organs. The heart and lungs and liver and stomach were all in their right places, but the texture felt dry and rough. What could have happened to this man?

Dozens of candles flickered in stands that Parris had drawn up all around the table, giving it the look of an altar with a ghoulish sacrifice. Outside the windows, all was dark. He began removing the organs one by one and setting them on the table, making notes of size and color and weight in his book. With so little decay, he could clearly see the difference between the veins and the arteries. He traced them with his fingers, from their origin in the heart and liver toward the extremities, where the blood was consumed by the rest of the body. He consulted ancient diagrams from Hippocrates and Galen to identify the smaller features.

There was a Belgian, Andreas Vesalius, who claimed that Galen was wrong, that the veins did not originate from the liver, but from the heart, just like the arteries. Saying Galen was wrong about anatomy was akin to saying the Pope was wrong about religion, but of course many people in England said that, too, these days. It was a new world. Parris lifted the lungs out of the way, and could see that Vesalius was right. Never before had he managed so clean and clear a view. He traced a major vein down toward the pelvis.

“Look at this,” Parris said, mostly to himself, but Felbrigg got up to see, wiping his beard and scattering crumbs into the dead man’s abdominal cavity. “The intestines are encrusted with white.” Parris touched a loop with his finger, and then tasted it. “Salt.”

“What was he doing, drinking seawater?” Felbrigg said.

“Only if he was a fool.”

“A thirsty man will do foolish things sometimes.”

Parris was thoughtful. “Maybe he did drink salt water. Maybe that’s why the body is so preserved.”

He lifted out the stomach, which was distended. The man had eaten a full meal before dying. Maybe what he ate would give a clue to his condition.

Parris slit the stomach and peeled it open, the grit that covered everything sticking to his hands. He stared at the contents, astonished.

“What is it?” Felbrigg asked.

In answer, Parris turned the stomach over, pouring a pile of pebbles and sand out onto the table.

Felbrigg laughed. “Maybe he thought he could turn stones into bread—and seawater into wine!” This put him into such convulsions of laughter that he choked and coughed for several minutes.

Parris ignored him. What had happened on that boat? This was not the body of a man who hadn’t eaten for days; he was fit and well nourished. What had motivated him to eat rocks and drink seawater? Was it suicide? Or had they all gone mad?

The sound of carriage wheels and the trot of a horse on packed earth interrupted his thoughts. Parris saw the fear in Felbrigg’s eyes and knew it was reflected in his own. The body could be hidden, perhaps, but the table was streaked with gore, and gobbets of gray tissue stained the sheet he had spread out on the floor. His clothes were sticky and his hands and knife fouled with dead flesh. King Edward had brought many religious reforms in his young reign, but he would not take Parris’s side on this. It was criminal desecration, if not sorcery. Men had been burned for less.

Parris started blowing out candles, hoping at least to darken the room, but he was too late. There were footsteps on the front steps. The door swung open.

But it wasn’t the sheriff, as he had feared. It was his wife.

Joan didn’t scream at the sight. To his knowledge she had never screamed, nor fainted, nor cried, not for any reason. Her eyes swept the room, taking in the scene, the body, the knife in his hands. For a moment they stood frozen, staring at each other. Then her eyes blazed.

“Get out,” she said, her voice brimming with fury. At first Felbrigg didn’t move, not realizing she was talking to him. “Get out of my house!”

“If you can bring any more like this one, I’ll pay you double,” Parris whispered.

Felbrigg nodded. He hurried past Joan, bowing apologies, and ran down the steps.

“How is it you’re traveling home at this hour?” said Parris. “Is the celebration over? Where’s Catherine?”

Another figure appeared in the doorway behind Joan, but it wasn’t his daughter. It was a man, dressed in a scarlet cloak hung rakishly off one shoulder, velvet hose, and a Spanish doublet with froths of lace erupting from the sleeves. Parris scowled. It was Francis Vaughan, a first cousin on his mother’s side, and it was not a face he wanted to see. Vaughan’s education had been funded by Parris’s father, but he had long since abandoned any career, preferring the life of a professional courtier. He was a flatterer, a gossipmonger, living off the king’s generosity and an occasional blackmail. His eyes swept the room, excitedly taking in the spectacle of the corpse and Parris still holding the knife.

“What are you doing here?” Parris said. The only time he ever saw his cousin was when Vaughan was short of cash and asking for another “loan,” which he would never repay.

“Your wife and daughter needed to return home in a hurry,” Vaughan said. “I was good enough to escort them.” He rubbed his hands together. “Cousin? Are you in trouble?”

“Not if you leave now and keep your mouth shut.”

“I’m not sure I can do that. Discovering the king’s own physic involved in . . . well. It’s big news. I think the king would want to know.”

Parris knew what Vaughan was after, and he didn’t want to haggle. He pulled a purse out of a drawer and tossed it to him. Vaughan caught it out of the air and peered inside. He grinned and disappeared back down the steps.

Joan glared at Parris, at the room, at the body. “Clean it up,” she hissed. “And for love of your life and mine, don’t miss anything.” The stairs thundered with her retreat.

But Parris had no intention of stopping. Not now, not when he was learning so much. He could deal with Vaughan. He’d have to give him more money, but Vaughan came by every few weeks or so asking for money anyway. He wasn’t ambitious enough to cause him real problems.

There were risks, yes. People were ever ready to attack and destroy what they didn’t understand, and young King Edward, devout as he was, would conclude the worst if he found out. But how would that ever change if no one was willing to try? He had a responsibility. Few doctors were as experienced as he was, few as well read or well connected with colleagues on the Continent. He’d even communicated with a few mussulman doctors from Istanbul and Africas who had an extraordinary understanding of the human body.

And that was the key—communication. Alchemists claimed to have vast knowledge, but it was hard to tell for sure, since they spent most of their time hiding what they knew or recording it in arcane ciphers. As a result, alchemical tomes were inscrutable puzzles that always hinted at knowledge without actually revealing it. Parris believed those with knowledge should publish it freely, so that others could make it grow.

But Joan didn’t understand any of this. All she cared about his profession was that it brought the king’s favor, particularly if it might lead to a good marriage for Catherine. And by “good,” she meant someone rich, with lands and prospects and a title. Someone who could raise their family a little bit higher. She was constantly pestering him to ask the king or the Duke of Northumberland for help in this regard, which was ludicrous. He was the king’s physic, the third son of a minor lord who had only inherited any land at all because his older two brothers had died. His contact with His Majesty was limited to poultices and bloodletting, not begging for the son of an earl for his only daughter.

He continued cutting and cataloging, amazed at how easily he could separate the organs and see their connections. Nearly finished, a thought occurred to him: What if, instead of being consumed by the flesh, the blood transported some essential mineral to it through the arteries, and then returned to the heart through the veins? Or instead of a mineral, perhaps it was heat the blood brought, since it began a hot red in the heart and returned to it blue as ice. He would write a letter to Vesalius.

When he was finished, he wrapped what was left of the body in a canvas bag and began to sew it shut. In the morning, his manservant would take it to a pauper’s grave, where no one would ask any questions, and bury it. As he sewed, unwanted images flashed through his mind. A bloodsoaked sheet. A young hand grasped tightly in his. A brow beaded with sweat. A dark mound of earth.

He must not think on it. Peter’s death was not his fault. There was no way he could have known.

His conscience mocked him. He was physic to the King of England! A master of the healing arts! And yet he couldn’t preserve the life of his own son, the one life more precious to him than any other?

No. He must not think on it.

Parris gritted his teeth and kept the bone needle moving up and down, up and down. Why had God given him this calling, and yet not given him enough knowledge to truly heal? There were answers to be found in the body; he knew there were, but they were too slow in coming. Too slow by far.

Quintessence © David Walton 2012